A diplomatic rite symbolising the landholder's hospitality, in which strangers were allowed temporary access to clan resources after a ritual exchange of gifts. Ian D Clark, 2003, p.117

A diplomatic rite symbolising the landholder's hospitality, in which strangers were allowed temporary access to clan resources after a ritual exchange of gifts. Ian D Clark, 2003, p.117

At this point, I can turn to Norbert Elias' argument about the civilizing process in Europe...essentially it came down to the attempt, largely on the part of middle class religious authorities, to improve the manners of those below: most of all by eliminating all traces of the carnivalesque from popular life. David Graeber, Possibilities, p31-32.

The Dancers Inherit the partyWhen I have talked for an hour I feel lousy –Not so when I have danced for an hour:The dancers inherit the partyWhile the talkers wear themselves out andsit in corners alone, and glower.

On middle class povertyThe poet's teeth are rotten.The poet doesn't drive.The poet has an empire in the mind.The poet writes the god.The poet is assassinated.The poet's unAustralian.Patrick Jones (listen to this poem here)

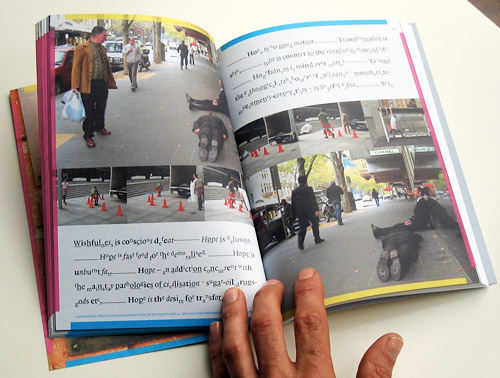

After I posted the most recent WorkmanJones film, Tag, a friend of mine, Hamish Morgan, challenged me on why we chose to use the city as a site for our work. There are so many ways to think about and address this question. I initially gave some reasons in response, but having thought more about it lately, about impermanent culture (impermaculture), I thought I'd share some of this thinking.

Firstly, cities exist. Modern cities are toxicities, they rely on resources from elsewhere, they waste waste, they can (probably) never be sustainable, more people live in them than in rural areas (a recent global phenomenon), and cities are places of social invention and mutation. For all these reasons, critiquing, participating in and understanding the city is to understand the dominant psyche of modern humans and why centralised capitalism is killing us, and many other species, very rapidly and very cruelly.

Recently, I voluntarily endured a paper given by a PhD candidate that cross-pollinated Situationist thought with her own desire to continue shopping. It was a seemingly clever paper using fashionable dérive poetics with individualist urbane desire. Michael Farrell brilliantly called it 'romantic shopping'. It simply repulsed me. She was a post-graduate student in sustainability and architecture.

Her intellectual abstractions represented her mediated blindness. She told us that she drove her car into the city to carry out her shopping 'experiments', and that she had to consume things in order for her experiment to work. When I challenged her, pretty clumsily regrettably, on her work as capitalist embellishing, she exclaimed, "But what other system have we got?"

What was so offensive about this paper was that an architect working in the area of sustainability was not looking at urban permaculture in Havana as a model or focus point for her research, or any other transitional city. Havana is a living example that excitingly challenges my Jensenian belief that cities can never be sustainable (based on a reliance upon the importation of resources). Instead it was her own desire and its place in the world that was being indulgently understood. The other area this paper failed to investigate, regarding the question of future sustainability and urban psychogeography, was indigenous intelligence.

If property is so closely related to avoidance, and if these two principals of identification and exclusion really are so consistently at play (and I think they are), then is it really so daring to suggest that the person, in the domain of avoidance, is constructed out of property? David Graeber, Possibilities, p22.

The one thing that everybody wants is to be free...not managed, threatened, directed, restrained, obliged, fearful, administered, they want none of these things they all want to feel free...they do not want to be afraid not more than is necessary in the ordinary business of living... Gertrude Stein, 1943

The one thing that everybody wants is to be free...not managed, threatened, directed, restrained, obliged, fearful, administered, they want none of these things they all want to feel free...they do not want to be afraid not more than is necessary in the ordinary business of living... Gertrude Stein, 1943

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure segregation in all public facilities, with a "separate but equal" status for black Americans and members of other non-white racial groups. (source: Wikipedia)

The origin of the phrase "Jim Crow" has often been attributed to "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of African Americans, which first surfaced in 1832. (source: Wikipedia)

Aborigines saw man as sharing a common life-principal with animals, birds and plants. They embraced all these in human social and religious life by establishing totemic relationships between them and people. (A P Elkin, 1967, from The Loddon Aborigines, Edgar Morrison, p.17., private press booklet, 1971, from articles published in the Daylesford Advocate newspaper 1963-1971).The Loddon Aborigines, as anthropologists like David Graeber might suggest, had relations of 'common substance' with the land – a closed-cycle, single-broken-line homeostasis, where the body (as tribe) is contiguous with everything else. Here, the closed-cycle represents the tribal land, a clearly delineated food and water bowl where nothing is wasted, and the single-broken-line represents the necessity for other relations outside of this land.

Within these clearly defined boundaries their hunting rights were ordinarily respected by their neighbours with whom they normally enjoyed friendly relations and a measure of collaboration and inter-marriage. (The Loddon Aborigines, Edgar Morrison, p16., private press booklet, 1971, from articles published in the Daylesford Advocate newspaper 1963-1971).This kind of collaboration can occur because the line is permanently broken. By contrast, the gated-existence model of industrial civilisation – the privatisation, capitalisation and transportation of resources – is represented as a solid double=white=line; a line of brutally imposed impermanent or throwaway culture.

The body in the domain of joking, one might say, is constituted mainly of substances – stuff flowing in or out. The same could hardly be true of the body in the domain of avoidance, which is set apart from the world... While joking bodies are necessarily apiece with the world (one is almost tempted to say "nature") and made up from the same sort of materials, the body in avoidance is constructed out of something completely different. It is constructed of property. p21.Relations of 'common substance' are also recalled.

...where an entirely material idiom of bodily stuff and substances can be seen as the basis for bonds of caring and mutual responsibility between human beings. p23.He goes on to talk about the possibility of sex between two people in terms of sharing food, not as one person consuming the other (as mentioned in an earlier post). Sharing, here, is experienced outside of an 'owning' relation (of avoidance). Graeber, like Hamish Morgan a few weeks ago in this garden, brings in Marcel Mauss.

Mauss has also argued that in giving a gift, one is giving a part of oneself. If a person is indeed made up of a collection of properties, this would certainly be true... Gift giving of the Maussian variety is never, to my knowledge, accompanied by the sort of behaviour typical of joking relations; but it often accompanies avoidance. p23.A double white Australia line policy, an expression fixé I have used in poems and other forms of thinking since 2001, is used to describe how colonialism (relations of avoidance) pierces and separates, disenfranchises and prepares Aboriginal land and resources for private use and sale. A double white Australia line is a policy of all governments since occupation.

Sexual relations, after all, need not be represented as a matter of one partner consuming the other; they can also be imagined as two people sharing food.More on Possibilities later.

You talk about in your 'How to do Words with Things' about city based artists feeding off their own disconnection/abstraction in order to do their art (I would have to check up on that); their angst becomes generative of the work itself, and because everyone in the city has this disconnection there is a good market for this kind of work. Consumers buy the art in order to express their solidarity with disconnection and consumption. Your play in the city (along with an interest in graffiti, tagging, fonting!), to me, expresses a critique of those kind of artistic practices. That is, an art practice not built around consumption, one that is decapitalised. You propose an exchange, or gift-ecology. (The idea of a gift-economy began with Marcel Mauss, an anthropologist writing in the late 1920s after the destruction of Europe – through war and the industrial revolution – and wanting to rediscover a point of human connection without economic and industrial subterfuge. His book, 'The Gift', is a rather interesting critique of capitalism). I digress, back to my long-winded point. So you are interested in an art practice that generates responsibilities, obligations, debts, counter-gifts that keep a cycle of exchange going, that connects and keeps us in play with each other. (Another side point, the word for gift in German 'Gib' is the same word as poison - i.e. the gift is not 'free' but indebts us to give back, which is not necessarily a bad thing. The gift; antidote and poison! Also the English derivative of gift comes from the same word as 'take': the gift economy is one where we give and take; by giving we take something from the other - we take their sense of debt so that they give back!).

Perhaps all I want to say is that a truly decapitalised practice would have nothing to do with the city; would have no play with its structures, because this is what gives and takes our (creative) energy. I love a good ideas stoush; this shows my terrible reliance on critique (this is what the university teaches). I retreat from creativity through the self-defense of critique - now there is another provocation... PJ, I might add, I find your work terribly hopeful and evocative of a post-industrial future. Please keep sharing and indebting us all in a gift-ecology.

If the fact of becoming an architect after having built castles in the sand, of becoming a butcher after having pulled the wings off flies, of becoming a professor after having stuck one's nose in books, if all that indicates an incapacity to grow up, then I agree...

My friend Bradley sent me George Orwell's essay 'Politics and the English Language' after seeing Best Sellers. In it Orwell argues for a written language that is not exporting surplus and waste. Here are the fast and hard rules:

i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

In less than a generation we have used half the world’s oil supply and are rapidly depleting other fossil fuels. Cheap food and cheap energy are becoming things of the past. The machinations of growth-obsessed industrial civilisation result in the continual transfer of carbon from the ground, where it is good, to the atmosphere, in ever-increasing quantities that make it toxic. Despite all the evidence demonstrating this, the governing corporations remain committed to the growth model - acting as though the environment has an infinite capacity to absorb the relentless production of toxicological wastes.

The Centre for Collective Wealth is a project-based initiative founded by Jason Workman and Larisa Marossine in Brooklyn, NY. The centre facilitates online projects, discussions, events, public works and shows.For its inaugural project, the Center for Collective Wealth presents Best Sellers, a new video work by Patrick Jones.

(Made from vegetable based inks printed on chlorine-free pulp - fully compostable!)

(Made from vegetable based inks printed on chlorine-free pulp - fully compostable!)